He grabbed $4,500, stuffed it into a fanny pack, fled a few blocks, hailed a taxi, and vanished into the streets. That was the beginning of a one-year bank robbery spree that saw him hit around two dozen banks across Southern California, collecting about $250,000, all without firing the .357 Magnum he kept tucked in his waistband.

If he could speak to his younger self, he wouldn’t lecture about avoiding crime. He knew it was wrong. He would simply tell himself to write—to use his words to find clarity and strength.

“When someone’s hurting, you don’t tell them to stop,” he says. “You meet them with compassion and help them find a way through.”

Banks A New Chapter with His Daughter

Today, Loya is a divorced father raising his teenage daughter, Matilde. Fatherhood, he admits, came with fear—fear that he might repeat the mistakes of his own father. But Matilde has become his reason to keep moving forward. He’s writing a new memoir, this time in the form of letters to her, exploring everything he’s learned—and all he still wrestles with.

“The violence ends with me,” Loya said.

His journey isn’t clean or simple. It’s layered with pain, regret, self-discovery, and hope. And while it may look like redemption from the outside, Loya knows it’s something far more complex: it’s a life examined, one chapter at a time.But for Loya, now 63 and living in Berkeley, California, this isn’t a simple story of crime and redemption. He has spent the past three decades not trying to erase his past but to understand it—and to help others do the same.

A Childhood Fueled by Fear, Grief, and Violence

Loya’s roots trace back to a complicated upbringing in East Los Angeles. His father, a Southern Baptist minister, ruled their home with a mixture of religious fervor and violent discipline. “I had to be perfect,” Loya recalled. He remembers his dad beating him with a belt for missing math questions and forcing him to recite multiplication tables after work.

His mother, gravely ill with kidney disease, was the only gentler presence. She died when Joe was just 9 years old, and with her death, the last protection against his father’s violence disappeared. At age 16, after enduring one particularly brutal beating, Joe grabbed a steak knife and stabbed his father in the neck.

Instead of anger, that moment brought reflection. His father later admitted on a podcast: “He didn’t stab you — you made him stab you.” Joe was briefly placed in foster care, but the damage was already done.

Becoming the “Beirut Bandit”

Joe began drifting into crime—stealing cars, forging documents, and conning people out of money. But he wanted more. Inspired by the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, who robbed banks and trains, Loya set his sights on becoming a modern-day outlaw.

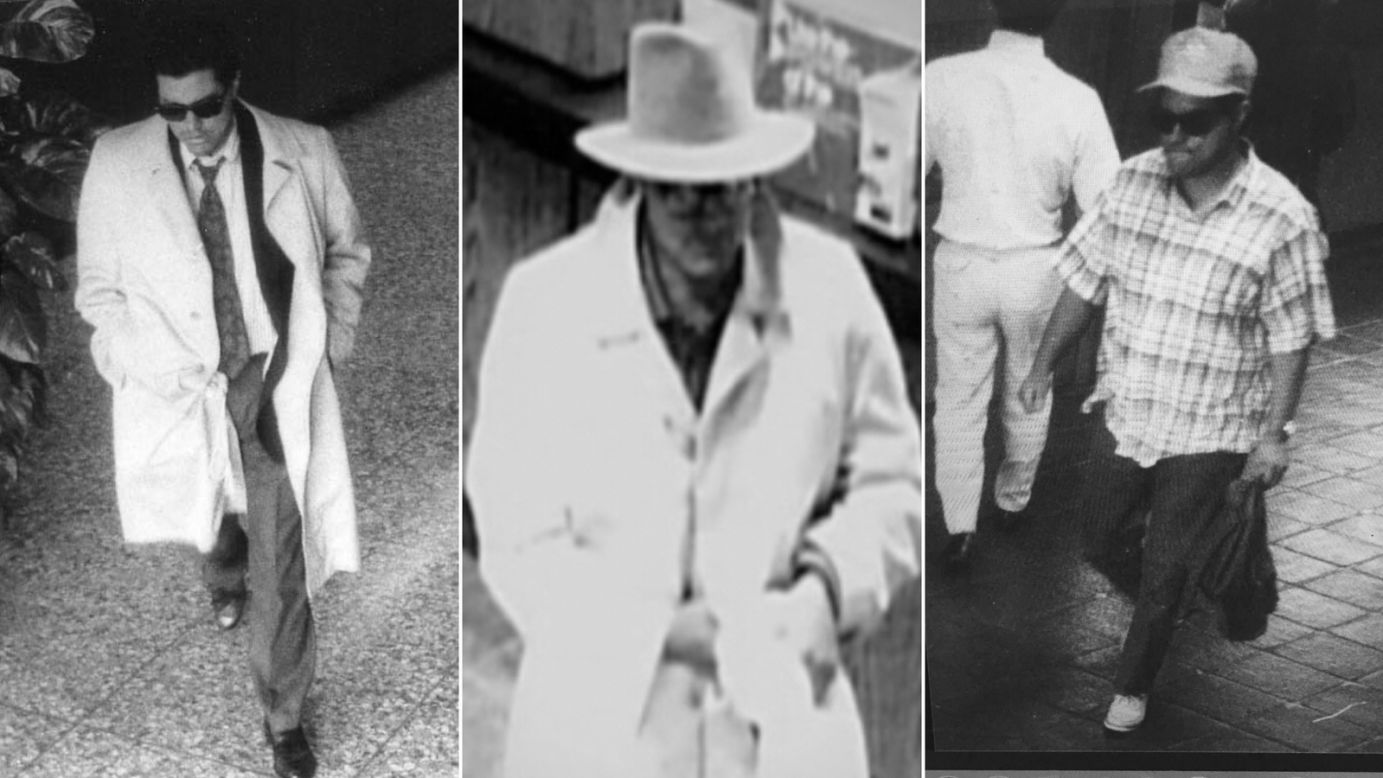

He dressed the part. Sometimes he wore a suit, other times shorts and layered clothes he could discard as he fled. He never left home without dark sunglasses, which became part of his disguise.

He researched banks near highways, used taxis as his getaway, and even managed multiple robberies in a single day.

But his spree ended in May 1989. Betrayed by a girlfriend, he was arrested on the UCLA campus, sipping a cappuccino as he waited to give her money and flee to Mexico.

Prison Didn’t Reform Him—At First

Loya was sentenced to seven years in prison after pleading guilty to three robberies. Behind bars, he continued to act out—smuggling drugs, fighting, and eventually landing in solitary confinement for two years after stabbing another inmate.

It was there, in the enforced silence of solitary, that something shifted. He started reflecting on his life and exchanging letters with his estranged father. Those conversations slowly opened the door to forgiveness—and to change.

The Guilt That Still Haunts Him

Loya has never apologized for robbing banks. “Banks are insured,” he says. “They’re fine.” But what troubles him deeply is the trauma he caused to the bank tellers—ordinary people who suddenly faced the fear of death.

He has never tried to contact them. Doing so, he believes, would only reopen old wounds.

A Life Reimagined—But Not Redeemed

After prison, Loya wrote a memoir called “The Man Who Outgrew His Prison Cell” and became the subject of a podcast titled “Get the Money and Run.” He now works as a writer, podcaster, and prison reform advocate, helping other inmates tell their stories and find meaning in their pasts.

But he resists the label of a “redemption story.”

Helping Others Reclaim Their Stories

Over the years, Loya has mentored former inmates and worked with prison programs alongside author Piper Kerman, whose memoir inspired Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black. He teaches inmates the power of storytelling—how owning your past can be the key to reshaping your future.

One former inmate, Rosario Zatarain, met Loya while in prison for drug and robbery charges. Initially skeptical, she was won over by his honesty and openness. Loya became her mentor, and today, she works as a drug and alcohol counselor, using her past to inspire others.

“In Joe, I saw someone who turned what the world condemned into a superpower,” Zatarain said. “He taught me that we don’t need to be accepted by society to be worthy.

Healing the Wounds of the Past

When Joe left prison, his father greeted him with a cake that read “Welcome Home Joey.” Over time, the two men rebuilt their relationship. They even visited prisons together to speak about forgiveness, rage, and healing.

“For me to change, I had to develop compassion—for myself and for him,” Loya said. “I had to understand where the violence came from.”

If he could speak to his younger self, he wouldn’t lecture about avoiding crime. He knew it was wrong. He would simply tell himself to write—to use his words to find clarity and strength.

“When someone’s hurting, you don’t tell them to stop,” he says. “You meet them with compassion and help them find a way through.”

A New Chapter with His Daughter

Today, Loya is a divorced father raising his teenage daughter, Matilde. Fatherhood, he admits, came with fear—fear that he might repeat the mistakes of his own father. But Matilde has become his reason to keep moving forward. He’s writing a new memoir, this time in the form of letters to her, exploring everything he’s learned—and all he still wrestles with.

“The violence ends with me,” Loya said.

His journey isn’t clean or simple. It’s layered with pain, regret, self-discovery, and hope. And while it may look like redemption from the outside, Loya knows it’s something far more complex: it’s a life examined, one chapter at a time.