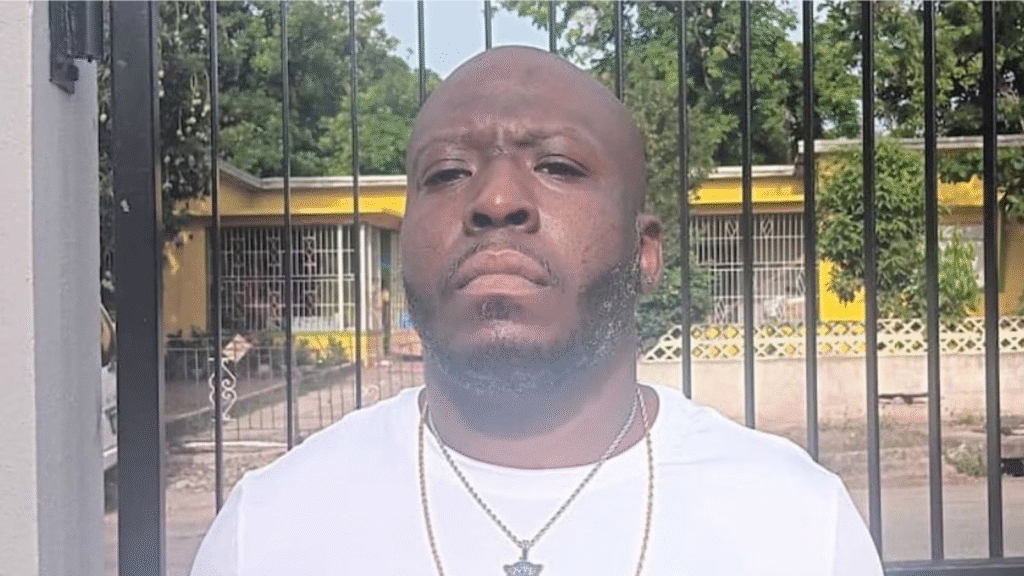

Born on a U.S. Army base in Germany to a U.S. citizen soldier, he believed he was American. He grew up in the United States, went to school here, worked here, and built his life here. But due to a complicated legal loophole tied to citizenship transmission laws and immigration enforcement policies, his life took a dramatic turn. Recently, he was forcibly removed from the only home he’s ever known and sent to Jamaica—a country with which he has no personal ties, no family, and no support network.

The deportation has raised serious concerns among immigration advocates, veterans’ groups, and legal experts, who argue that this case highlights the flaws in U.S. immigration and nationality law, especially for children born abroad to American service members. They say cases like his are not isolated and that many individuals who should qualify for U.S. citizenship fall through the cracks due to outdated or overly rigid legal interpretations.

Now in Jamaica, the man is struggling to adjust to a foreign land. He is grappling with the loss of his community, job, and family back in the U.S.—and fighting to return to the country he has always called home.

Man Born on U.S. Military Base to American Soldier Deported to Jamaica—A Country He’s Never Known

“I just think to myself, this can’t really be happening,” Thomas told CNN from a homeless shelter in Kingston, where he now lives, alone and stateless.

Stateless and Stranded

Legally, Thomas is stateless. Though his father was a naturalized American citizen and longtime military servicemember, Thomas does not qualify for citizenship in the U.S., Germany (his birthplace), Kenya (his mother’s birthplace), or Jamaica (his father’s birthplace). According to records reviewed by CNN, his father became a U.S. citizen in 1984, two years before Thomas was born. The family returned to the U.S. in 1989, and young Jermaine entered as a legal permanent resident. But a visa form mistakenly listed his nationality as Jamaican.

Now, decades later, that clerical detail, combined with a web of legal complexities, has determined his fate.

A Life in America, a Future in Limbo

Thomas grew up in Florida and Virginia and spent most of his adult life in Texas, working odd jobs—construction, cleaning, car washing—while struggling with housing instability and untreated mental health issues. Diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, Thomas was prescribed psychiatric medication in the U.S., which he says is now running out in Jamaica.

He also has a criminal history, including drug possession, robbery, and other charges dating back to 2006. He served several sentences, including a recent term from 2020 to 2023 for driving while intoxicated and harassment of a public servant.

When that sentence ended, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents took custody of him.

Deported Without Warning

Thomas says he was transferred between facilities with little explanation. Eventually, ICE officers placed him in a cell with men scheduled for deportation to Nicaragua. When he protested that he was not a foreign national, he says officials told him he was being sent to Jamaica.

On May 28, with only the clothes he was wearing, Thomas was forcibly deported—escorted by ten U.S. Marshals on the flight, according to his account.

“All hope was lost,” he said. “I didn’t see a future.”

A Legal Gray Zone

Thomas’s case raises difficult legal questions about birthright citizenship, the rights of children born to U.S. citizens abroad, and the status of U.S. military bases. His attorneys argued he was a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment, having been born on a U.S. military base to a U.S. citizen parent. But in 2015, a federal appeals court ruled that military bases overseas do not qualify as U.S. soil under the Constitution.

If Thomas had been born just one year later—when the law changed—he would have been a U.S. citizen.

Even a comparison with the late Senator John McCain, who was born on a U.S. military base in the Panama Canal Zone, didn’t sway the courts. The key legal difference: McCain was born in a U.S. sovereign territory, while Thomas was not.

In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Thomas’s appeal, ending his bid for recognition as a U.S. citizen.

Family in Fear, System in Question

Thomas’s family members, who remain in the U.S., are afraid to visit him in Jamaica for fear of being caught in ongoing deportation crackdowns under directives from the Trump-era immigration agenda.

“My question is, why would you hold a child responsible for something that he had no control over or knowledge of?” one relative asked.

They acknowledge Thomas has made mistakes but argue that he should be held accountable in the country he’s lived in all his life—not banished to a foreign land.

No Country to Call Home

Thomas has no legal status in Jamaica. According to a letter from the Jamaican consulate in Miami, he must formally apply for citizenship based on his father’s nationality—something he says he does not plan to do. “My life, my kids, my family is back in the States,” he said.

“Jamaica is not a bad place. It’s just not the place for me. I don’t belong here.”

Statelessness: A Growing Concern

Immigration experts say cases like Thomas’s, though rare, are growing more visible. Betsy Fisher, an immigration attorney and lecturer at the University of Michigan, explained that stateless individuals exist in a legal vacuum. They are not recognized as nationals by any country, making them extremely vulnerable to deportation, detention, and denial of rights.

“Legally, Thomas has likely been stateless his whole life,” Fisher said. “His situation falls into the cracks between ways of acquiring U.S. citizenship. Unfortunately, those cracks are devastating when someone falls through.”

A Final Plea

Thomas is still trying to process how the country he always believed was his could cast him out so suddenly.

For Thomas, exile feels like a lifetime sentence. “What are you supposed to do when you’re stateless?” he asks. “You lose your identity, your future—everything.”

Stateless and Stranded: U.S. Deports Man to Country Where He Has No Legal Status

In the case of Jermaine Thomas, deported from the United States to Jamaica despite no legal connection to the country, experts say his story exposes a growing and deeply troubling legal and humanitarian gap: the treatment of stateless individuals by the U.S. immigration system.

According to immigration experts, current U.S. law does not require a person to have citizenship or even legal status in the country to which they are deported. The U.S. is also not a signatory to either of the two United Nations conventions on statelessness, which aim to protect people who are not considered citizens by any country. Still, deporting someone to a nation where they have no legal ties is considered rare and troubling.

“It’s a fairly recent phenomenon that a stateless person would be deported to a country where they don’t have any legal connection,” one legal expert told CNN.

She added that while some progress had been made under the Biden administration to recognize and protect stateless individuals within the U.S., those efforts have since been reversed under policies reinstated during Donald Trump’s presidency. “We’re really moving backward on this issue,” she said. “It’s something Congress could fix very quickly if there was the political will.”

For Thomas and others like him, the consequences are devastating.

“Like a Life Sentence”

Thomas’s family describes his current status as nothing short of a life sentence. “You live on the fringes of society,” one relative said. “You don’t have any legal standing that allows you to work, to rent a place to live, to do anything.”

Now homeless in a foreign land, Thomas wakes up every day in the suffocating heat of Kingston, Jamaica—hundreds of miles from his children, his relatives, and the only home he’s ever known. “It takes me a while every morning to realize this is real,” he told CNN. “It feels like a nightmare, but I’m really here.”

Initially, the Jamaican Ministry of National Security provided him with a temporary hotel room. But that support ended. He now lives in a crowded homeless shelter where he says life is chaotic, uncomfortable, and exhausting.

“I’m always hungry, completely exhausted, and constantly on edge,” Thomas said. He has no legal documentation in Jamaica, meaning he can’t apply for a job or even get a government-issued ID.

Though he says many locals have been respectful and kind, the language barrier adds to his isolation. Most people speak Jamaican Patois—a dialect he struggles to understand.

Family Left Behind

Thomas’s loved ones back in the United States are heartbroken—and afraid. Some family members, who are not U.S. citizens themselves, told CNN they would like to visit him, but fear doing so might prevent them from being allowed back into the country.

“It’s horrible to see him suffer and not be able to help,” one family member said. They keep in touch with Thomas through daily messages on social media, but that’s the only connection they have left. “It’s like I’ve lost him forever. I’ll never go to Jamaica, because I don’t think I’d be let back into the U.S.”

Thomas said what he misses most is the feeling of belonging—of being free and at home. Despite a life marked by hardship, incarceration, and mental health challenges, he still sees the United States as his true home.

For now, that answer remains uncertain.

His case underscores the profound gaps in U.S. immigration policy when it comes to people who fall into legal limbo—those born to American parents in complex international circumstances, especially on military bases overseas. While his deportation might have followed the letter of the law, it has left Thomas without a country, without rights, and without a clear future.

Until laws are reformed, experts warn, more stateless individuals may face the same fate—forced into exile in countries they’ve never known, with no legal path to rebuild their lives.