Laws Sean “Diddy” Combs Acquittal Renews Focus on Survivors’ Rights and Legal Loopholes

The verdict is a disappointment to many advocates but has reignited a broader conversation about the legal systems survivors must navigate and the hard-fought victories won through recent reforms.

This law, and others like it, gave survivors a limited window to bring forward cases long considered closed. It became a lifeline for thousands who had previously been silenced by time restrictions embedded in the legal system.

Lookback Laws: A Brief Window to Seek Justice

New York’s Adult Survivors Act, passed in 2022, was part of a wave of legislative reform in states like New York and California. These laws introduced “lookback windows,” time-limited opportunities for adult and child survivors of sexual assault to file civil lawsuits, regardless of when the abuse occurred.

During that window—later extended due to the pandemic—nearly 11,000 lawsuits were filed in New York alone.

These reforms were directly influenced by the #MeToo movement, which went viral in 2017 and brought unprecedented public attention to stories of sexual abuse, especially within powerful institutions and industries.

Thousands File Claims—From Institutions to Celebrities

Under these lookback laws, lawsuits flooded in against high-profile individuals and institutions, including former President Donald Trump, convicted producer Harvey Weinstein, the Boy Scouts of America, and religious organizations like the Archdiocese of New York.

E. Jean Carroll, a former magazine columnist, used the Adult Survivors Act to sue Trump for rape and defamation. A Manhattan jury later found Trump liable for sexual abuse and awarded Carroll $5 million in damages—a case Rosenthal called a point of pride for the legislation.

“These laws helped bring down some of the most powerful people,” she said.

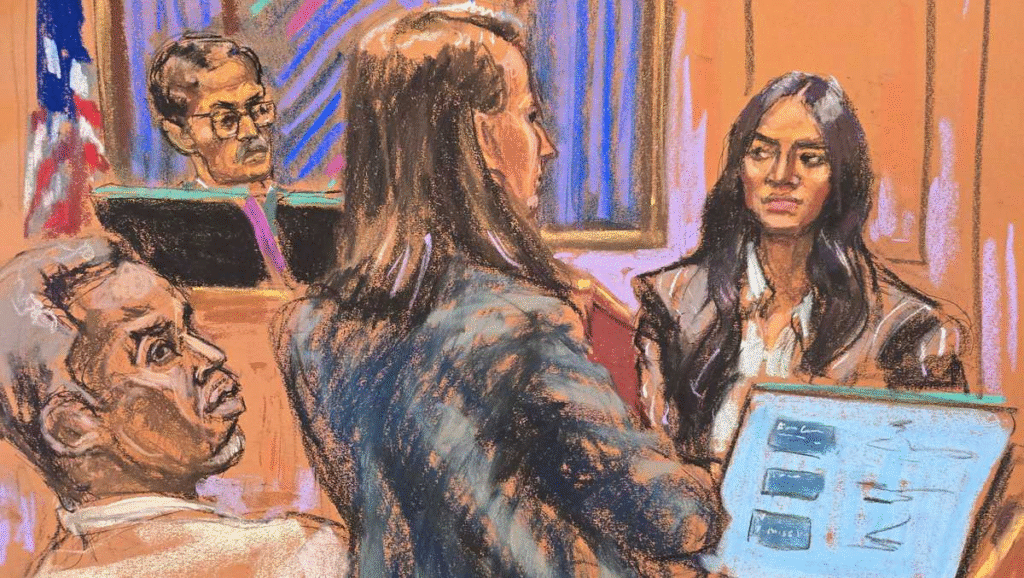

Ventura’s decision to pursue a civil case, knowing it would become public, also reflects the risks survivors take. Her lawyer, Doug Wigdor, said she had been offered an eight-figure settlement in exchange for silence but chose instead to file a lawsuit and expose Combs’ alleged abuse.

“She showed great courage, great bravery,” Wigdor said.

The Law Still Falls Short

But advocates stress that temporary legal windows are not enough. Survivors often need years—or decades—to process trauma and feel safe coming forward. A single year to file a case, especially one involving emotional pain and possible retaliation, isn’t always realistic.

Michael Polenberg, vice president of government affairs for the victim support nonprofit Safe Horizon, criticized the system as arbitrary and often inaccessible.

“Even with lookback windows, some survivors hit brick walls,” he said.

For example, some women assaulted while incarcerated in New York prisons must file their claims in the state’s Court of Claims, which requires highly specific details—such as exact dates and times of abuse. Many survivors, especially those traumatized and isolated for years, simply can’t meet that standard, leading to dismissals.

Polenberg noted that a majority of Adult Survivors Act cases were brought by formerly incarcerated women. “It’s unfathomable to ask someone to recall the precise date of an assault that happened while they were locked up for years,” he said.

Rosenthal introduced a bill to address this procedural issue, but it failed to advance this year.

Inconsistent Protections Across the U.S.

Nationwide, protections for survivors vary widely. Only a handful of states—including Kentucky, Virginia, and South Carolina—have removed the statute of limitations for all felony sex crimes, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). Others still maintain rigid time frames or temporary windows that close quickly.

Some states, until recently, included so-called “intoxication loopholes.” These allowed prosecutors to argue that voluntarily intoxicated victims had consented to sex, even if they were incapacitated.

Texas only closed its loophole in June 2025, expanding the definition of consent to include cases where someone is too impaired to give it. A similar bill in New York, backed by Rosenthal, failed.

This was personal for Christina Maxwell, a singer and actress in New York who said she was sexually assaulted at a workplace event in 2020 after drinking a beverage she believes was drugged. Despite video evidence and a police report, prosecutors declined to pursue her case.

She continued working at the same company for three years afterward, determined not to let the incident rob her of a dream career. Now, she advocates for stronger laws and has joined forces with Rosenthal and other lawmakers.

A Movement at a Crossroads

After years of intense public focus, media coverage has waned, and legislative support has cooled. Survivors and their allies must now fight to maintain attention and push for permanent reforms.

Tarana Burke, founder of the #MeToo movement, emphasized that even if the criminal verdicts don’t go the way survivors hope, their impact is lasting.

“We all listened to Cassie. We all saw that video. We’ve heard that testimony—it’s not going anywhere.”

Looking Ahead

The verdict in Combs’ case may not have delivered the accountability some had hoped for, but it reaffirmed the power of survivors willing to speak up and challenge a broken system. Their efforts, made possible in part by temporary legal changes, are now prompting a push for broader, lasting reform.

As advocates continue their uphill battle, one thing is clear: the struggle for justice is far from over, and every survivor who steps forward helps shape the path forward—for themselves, and for others still waiting to be heard.